I’ve written a book that many people find controversial, called State of Fear, and I want to tell you how I came to write it, because up until about five years ago, I had very conventional ideas about the environment and the environmental movement. This book really began in 1998, when I decided to write a novel about a global disaster. That was one of the first books I’d written, and I thought, well, I’m old now. I’ll write another one.

And in the course of my preparation for this book, I rather casually reviewed what had happened at Chernobyl, because I regard Chernobyl as the largest manmade disaster that I knew about. What I discovered stunned me. Chernobyl was a tragic event, but nothing remotely close to the global catastrophe that I was imagining. About 50 people had died in Chernobyl, roughly the number of Americans that die every day in traffic accidents. I don’t mean to be gruesome, but it was a setback for me. You can’t write a novel about a global disaster in which only 50 people die.

I was undaunted. I began to research other kinds of disasters that might fulfill my novelistic requirements, and that’s when I began to realize how big our planet really is and how resilient its systems ordinarily seem to be. Even though I wanted to create a fictional catastrophe of global proportions, I found it hard to come up with a credible example. I couldn’t actually come up with anything that I would believe, so in the end, I set the book aside and wrote something else.

But the shock that I had experienced reverberated in me for a while, because what I’d been led to believe about Chernobyl was not merely wrong. It was astonishingly wrong. Let’s review that for a minute.

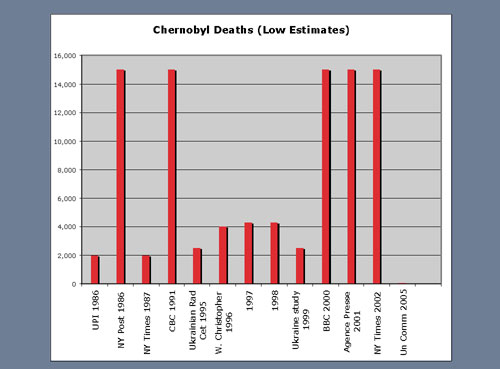

These are the low estimates of immediate Chernobyl deaths as a consequence of the actual incident, and you see here the UPI in 1986, at the time of the disaster, predicted that there would be 2,000 immediate deaths. The New York Post thought there would be 16,000. The Canadian Broadcasting Company in ’91 thought there would be that many, and you see the BBC and The New York Times in 2002 predicting at the low end 15,000 deaths. Their estimates were 15,000 to 30,000 deaths.

Now, there was a UN commission in 2000 that suggested that the catastrophe was nowhere near that proportion, and as you can see, the next UN commission in 2005 doesn’t really show up on the graph, because the total numbers are 56.

Now, to report that 15,000 to 30,000 people are dead when the actual number is 56 represents a very large error.

To get some idea of just how big, let’s imagine that we lined all the victims up in a row. If 56 people are each represented by one foot of space, then that’s probably the distance from me to about the second table here, something like that. Fifteen thousand people is three miles away. It seems difficult to make a mistake of that scale.

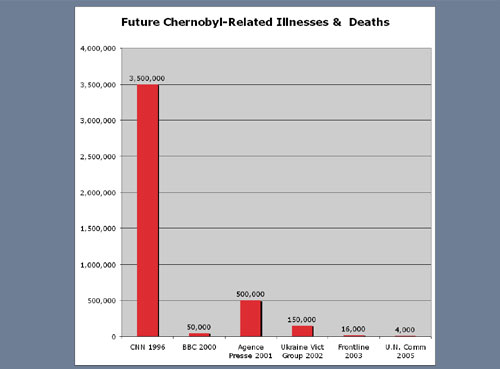

But of course, you’re probably thinking, we’re talking about radiation. What about long-term consequences? Unfortunately for the media, their reports are even less accurate here. Here you see CNN in 1996 was predicting future Chernobyl-related illness and death in a large swath that would go from Sweden to the Baltic to the Black Sea. It estimated three and a half million. The BBC, much more conservatively, estimated 50,000. Agence Press thought half a million. The Ukrainian Victim’s Group in 2002 estimated 150,000. The UN commission in 2005 decided that there would be about 4,000. That’s the number of Americans who die of adverse drug reactions in this country every six weeks. Again, a huge error.

But most troubling of all, according to the UN report, was that the largest public health problem created by the accident was the damaging psychological impact due to a lack of accurate information.

This was manifesting as—they said—negative self-assessments of health, belief in a shortened life expectancy, lack of initiative and dependency on assistance from the state. In other words, the greatest damage to the people of Chernobyl was caused by bad information. These people weren’t blighted by radiation so much as by terrifying, but false, information.

We ought to ponder for a minute exactly what that implies. We demand strict controls on radiation because it’s such a health hazard, but clearly Chernobyl suggests that false information can be a health hazard as damaging as radiation.

I’m not saying that radiation is not a threat. I’m also not saying that Chernobyl is not a genuinely serious event. But thousands of Ukrainians who didn’t die were made invalids out of fear. They were told to be afraid. They were told they were going to die when they weren’t. They were told their children would be deformed when they weren’t. They were told they couldn’t have children when they could. They were authoritatively promised a future of cancer, deformities, pain and decay. It’s no wonder they responded as they did.

In fact, we really need to recognize that this kind of human response is very well documented. Authoritatively telling people they are going to die can in itself be fatal.*

*http://www.blogger.com/post-edit.g?blogID=6086943054753240916&postID=1990535091945609235

Never forget 9/11 lies.

ReplyDeleteStudy prevailing winds.

Traditional cooling not possible.

Containment has been breached.

Dishonest governments never tell the truth.

Corrupt controlled media never tell the truth.